Stress, Wellness & Physiology

For many city residents, stress is a constant. Tragic or traumatic situations and events may disrupt people’s lives, but everyday, persistent stressors may have a greater impact on health and well-being for most people. Chronic stressors include financial strain, complex family interactions, and extended commutes. Research shows that nature experiences provide an antidote to stress and support general wellness, offering restorative experiences that ease the mind and heal the body.

Fast Facts

- The World Health Organization identifies stress and low physical activity as two of the leading contributors to premature death in developed nations.26,27

- The cumulative effect of chronic, low-grade stresses can have a greater impact on health and well-being than acute or extreme events that occur at infrequent intervals. Humans are able to manage moderate and high stress levels for a short period of time. Chronic stress, with little opportunity for recovery, can lead to unhealthy levels of psychological and physiological reaction.13,82

- Exposure to nearby nature can effectively reduce stress,33,79 particularly if initial stress levels are high.31 Simply having a view of nature produces recovery benefits.

- Individuals experience a greater degree of restorative experience and lower stress levels with greater duration and frequency of visits to green spaces.39

- Exercising in a green environment appears to enhance the restorative effects of urban greenery,37 and more restorative outdoor settings may boost exercise frequency.59

- Public housing residents with nearby trees and grass were more effective in coping with major life issues compared to those with homes surrounded by concrete.35

- Exposure to nearby green space and trees may have a positive effect on infant birth weight,47 particularly for lower socioeconomic groups.48

- Outdoor stewardship volunteering is positively related to physical activity and self-reported health and depressive symptoms, especially among mid-life volunteers.62

- Physical and perceived stress levels decreased significantly among those individuals between 50 and 88 years old who maintained a community garden plot compared with those who exercised indoors, suggesting benefits of gardening activity for healthy aging.64

- Studies in Japan of Shinrin-yoku, or forest walking, have found effects of improved immune system response, lowered stress indicators, reduced depression, and lower glucose levels in diabetics.19,83

Contents:

> Nature & Human Wellness > Stress & Health Effects * Stress Response * Urban Life & Chronic Stress * Health Effects > Nature & Stress Recovery > Public Health Concerns > Nature for Wellness * General Findings * Health & Nearby Green Space * Restorative Experiences * Outdoor Activity & Wellness * Cardiovascular and Respiratory Illness > Community Gardening > Shinrin-yoku or Forest Walking & Breathing > Theories About Restorative Nature Effects > References *cite: Wolf, K.L., S. Krueger, and M.A. Rozance. 2014. Stress, Wellness & Physiology - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health (www.greenhealth.washington.edu). College of the Environment, University of Washington.

Project support was provided by 1) the national Urban and Community Forestry program of the USDA Forest Service, State and Private Forestry, and 2) the Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service.

Nature & Human Wellness

Observations about nature as an antidote for the negative effects of city living date back centuries.1 Residents of ancient Rome noted that contact with nature helps one cope with urban noise and congestion.2 Medical professionals of the late-nineteenth century championed the urban park movement, finding strong correlation between green spaces and wellness.3 More recently, such intuitions are confirmed by scientific measures of human stress and physiological response. Green landscapes provide restorative settings that allow people to recover from daily and chronic stressors.4 Living near green areas, having a view of vegetation, and spending time in urban natural settings can reduce stress, and contribute to enhanced wellness for city dwellers. Below is a summary of the scientific studies.

Stress & Health Effects

Stress is a reaction to personal challenges, demands, and immediate threats. Stress responses can include psychological, physiological and behavioral components.5 Unresolved, long-term stress poses multiple challenges to human health.

Stress Response

The region of the brain that reacts to stress is directly linked to the autonomic nervous system,6 which controls basic physiological functions. When our bodies become stressed, our attention heightens, muscle tension increases, blood pressure rises, the pulse quickens, respiration increases, the digestive system slows, and one’s body produces more adrenaline.6

Stress reactions are deeply rooted and primal. The “fight or flight” response often determined survival in the early history of humans.6 In today’s urban settings, dangerous situations are no longer the most common source of stress. Yet our body’s systems respond in similar ways to the ongoing, ever-present stresses in our modern lifestyles, and there are few opportunities for recovery. Cumulative “daily hassles” can have a greater impact on health and well-being than less common acute stress events.7

Urban Life & Chronic Stress

Everyday stress factors in modern society can include financial strain, work demands, job loss, complex family interactions, marital conflict, and other persistent situations.8 In urban environments, people are often overloaded and over-stimulated by noise, movement, and visual complexity.9 Such daily interactions can overwhelm people.9 People who are raised in urban environments experience increased risk for mental health disorders.10

Another source of stress in contemporary everyday life is the feeling of disconnect between what we can accomplish and what we perceive is expected of us, especially in the work place.6 This can lead to feeling a lack of control in one’s life.6 Surveys indicate that 40% of U.S. workers experience stress in their workplace, and most people today believe they experience more stress than people did one generation ago.11 One result is anger, which can contribute to poor work performance, absenteeism, and increased turnover.12

Combined, life stressors lead to conditions of chronic stress. Chronic stress occurs when a person is exposed to mild or major stressors for a prolonged period of time with no opportunity for recovery, and then feels that he or she has no control over that situation.13 Individuals of lower socioeconomic status often experience a disproportionate amount chronic stress due to little control over work conditions, as well as higher exposure to violence, unemployment, and crime.14

Health Effects

Humans are able to manage both moderate and high stress levels for a short period of time. However, individuals experiencing ongoing, chronic stress are more likely to suffer from sleep problems, loss of appetite, stiff muscles, and other physical effects.15 Long-term exhaustion and significant stress reactions can lead to harmful effects on the cardiovascular and neuro-hormonal systems, memory impairment, and increased incidence of type II diabetes.16,17,18 Long-term psychological effects are another stress response. Maintaining mental health is one of the important issues related to disease prevention in developed countries.19

Nature & Stress Recovery

The experience of nature appears to be an antidote to the stress effects of urban living. Some scientists use an experimental setting to study responses. Participants are asked to complete a task within controlled conditions, and their physiological responses are monitored.

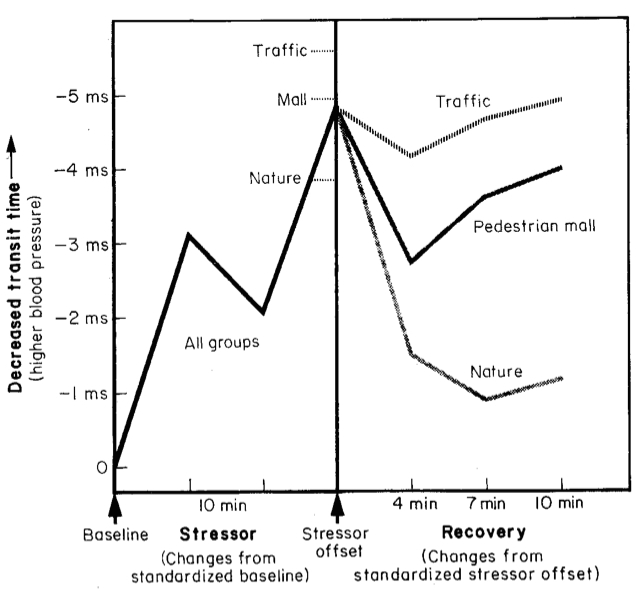

In 1991, Roger Ulrich and colleagues conducted one of the earliest and most often cited studies.4 Researchers presented a stressful movie to subjects and then each individual viewed one of six videos depicting various urban and natural environments. Data was obtained using both self-rating of stress levels and physiological indicators: heart period, muscle tension, skin conductance, and pulse transit time (which correlates with systolic blood pressure). Individuals who viewed natural versus built settings experienced more rapid and complete recovery. Stress recovery from nature views happened remarkably fast—in about 4 minutes —as can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Stress recovery rates when viewing different urban settings (using pulse transit time as a physiological stress indicator).4

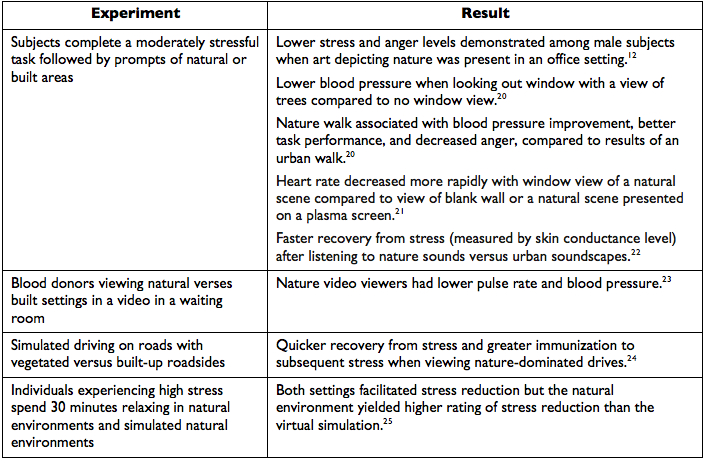

Other studies followed. Table 1 reports the research findings.

Table 1: Positive effects of nearby nature experiences in cities.

Public Health Concerns

Public health officials are concerned, as stress is increasingly the source of community health problems, general burnout and depression, and lowered overall human productivity.6 The World Health Organization identifies stress and low physical activity as two of the leading contributors to premature death in developed nations.26,27 Stress impacts in developed nations can be the source of significant expenses. For example, in 2001 the public costs in Sweden of stress-related disease were calculated to be about $13.5 billion (U.S.) for the nation's 10 million people.28 In today’s high tech, urbanized societies, stress is one of the most important factors contributing to ill health.6

There are other major public health concerns. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control reports that chronic diseases are among the most prevalent, costly, and preventable of all health problems. Such diseases include: arthritis, asthma, cancer, cardiovascular diseases (congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, hypertension, stroke, and other cerebrovascular disease), depression, and diabetes. In 2005, 133 million Americans – almost 1 out of every 2 adults – had at least one chronic illness.29 Chronic diseases take their toll on people at tremendous public cost.

Nature for Wellness

Certain risk behaviors—lack of physical activity, poor nutrition, tobacco use, and excessive alcohol consumption—are responsible for much of the illness, suffering, and early death related to chronic diseases.30 Lifestyle and behavior choices are important for overall personal health. Yet a wide range of studies conclude that nature views and experiences also contribute to reductions in chronic disease. The underlying mechanisms of the positive effects are not well understood. Yet associations between nature elements and health outcomes are supported by high-quality studies. Across the research, level of exposure to urban green space (or dosage) is expressed in terms of the quantity of nearby nature, distance to an amenity, the amount of time spent in the space, and the quality of the green space. Here are highlights of the findings.

General Findings

Passive experiences (such as views from a window or while walking nearby) of trees, parks, and gardens can effectively reduce stress.31,32 This effect is increased if initial stress or anxiety levels are high.33,34 For example, public housing residents with nearby trees and grass were more effective in coping with stressful major life issues compared to those with homes surrounded by concrete.35 Women may respond more positively to neighborhood green space.34 Some studies indicate that people may feel psychologically restored simply by looking at a photograph of a natural scene.21 People experiencing high stress can also benefit from being physically active in a nature setting.31,36

Health & Nearby Green Space

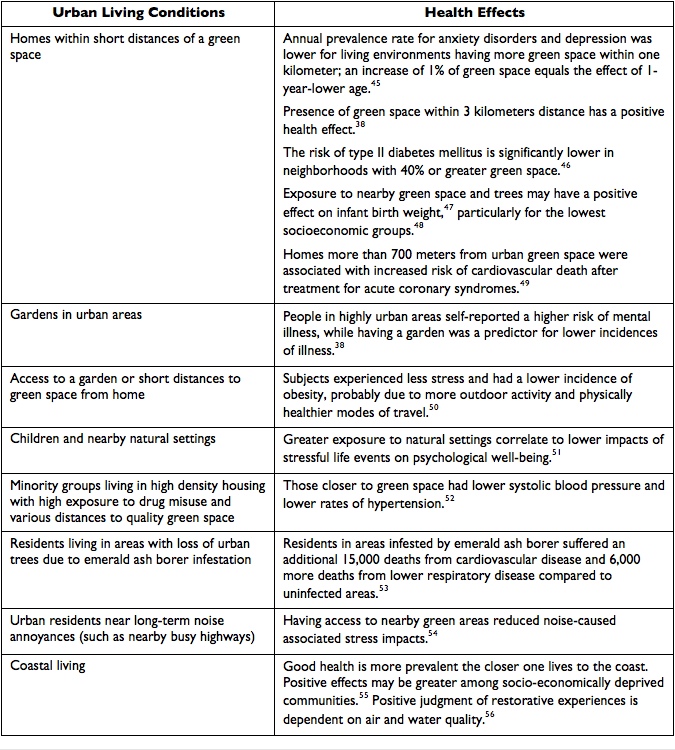

Studies on nature and health find differences among urban dwellers relative to their access to green space.38,6 Persons living near a green space probably have more frequent encounters, and benefits are therefore greater. Generally, with greater duration and frequency of visits to green spaces, individuals experience a greater degree of restorative experience and lower stress levels.39 The quality of green space also enhances restorative recovery, such as the density of forest canopy in an urban park.40 Parks may contribute more positive health impacts than overall neighborhood vegetation.41 Generally, the larger the park or green space, the greater the observed benefits,42,43 though attention to the character and quality of the space is important.44 Table 2 summarizes results from additional studies.

Table 2: Positive health outcomes associated with urban nearby nature experiences.

Restorative Experiences

Studies have also explored the sense of respite and recovery associated with time spent in and around urban green space.57 Urban environments with natural elements are more likely to support restorative reactions.58 In one multi-measure study the amount of time spent by people in an urban green space and visit frequency were both positively related to reported mental restoration; increase in length of stay from 0.5-1 hour to 1-1.5 hours increased the restorative effect. Additionally, the more an individual was stressed prior to the green space visit, the greater the degree of stress recovery. Finally, individuals who had previous experiences in natural settings (such as nature hobbies or childhood exposure) had greater restorative experiences than individuals with limited prior nature experiences.39

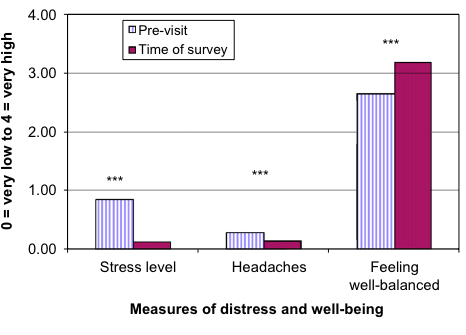

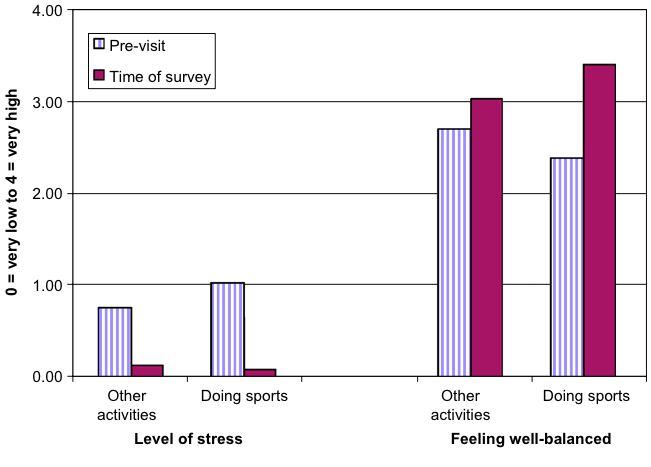

Figure 2: Respondents’ mean ratings of stress levels, headaches, and feeling well-balanced before visiting green space and at time of survey while in an urban green space.37

Cardiovascular & Respiratory Illness

Some of the more recent research has focused on major adult diseases. In a study of millions of adults in the U.K. and green space near their homes, it was found that male cardiovascular disease and respiratory disease mortality rates decreased with increasing green space, but no significant associations were found for women.84 Another study on the access to and use of larger, forested city parks found that the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and the prevalence of diabetes mellitus were significantly lower among park users than among non-users.85 One study used the loss of urban forest canopy due to Emerald Ash Borer infestation as a natural experiment in the U.S. Based on county-level health records there was an increase in mortality related to cardiovascular and lower-respiratory-tract illness in counties experiencing radical tree loss; the magnitude of this effect was greater as infestation progressed and in counties with above-average median household income.86

Outdoor Activity & Wellness

Frequent moderate exercise (or active living) provides wellness benefits, such as weight reduction and reduced stress. Exercising in a green environment appears to enhance the restorative effects of urban greenery,37 and more restorative outdoor settings may boost exercise frequency.59 Research suggests that stress reduction is enhanced when people recreate in natural environments that are familiar to them.60 The type of activity while in a green space makes a difference; one study found that positive effects increased with length of visit and for people doing active sports (e.g., jogging, biking, playing ball) compared to those engaged in less strenuous activities (e.g., taking a walk or relaxing)(see Figure 2).37 When comparing individuals doing a recreactional climb of a forest tree versus a concrete tower of the same height, tree climbers were more relaxed; experienced greater vitality; and expressed reduced tension, confusion, and fatigue.61 Outdoor volunteer stewardship helps to restore and conserve urban ecosystems; outdoor volunteering is also positively related to physical activity and self-reported health and depressive symptoms, especially among mid-life volunteers.62

Figure 3: Comparing activities with restorative outcomes in urban green space.37 Simply being in a green space decreased stress levels. Then, those people who were doing sports reduced stress more, compared to those pursuing less-strenuous (other) activities.

Community Gardening

Though less studied, community gardens in urban settings also provide wellness benefits. Gardeners find that gardening activity, combined with a natural setting, is relaxing and calming.63 Participants in one study viewed their community gardens as spaces of retreat within crowded neighborhoods, and attributed feelings of lower stress and a greater sense of well-being to the gardening experience.63 Physical and perceived stress levels decreased significantly among those individuals between 50 and 88 years old who maintained a community garden plot compared with those who exercised indoors, suggesting benefits of gardening activity for healthy aging.64

Shinrin-yoku or Forest Bathing

Long a tradition in Japanese culture, many people travel outside of the city to walk in forests on weekends. Shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, produces both physiological and psychological benefits.65,19 For diabetic patients, walking in a forest was more effective at decreasing blood glucose levels than other forms of exercise, such as walking on a treadmill.66 Forest walking participants have higher activity levels in the immune system cells that act to reject tumors and cells infected by viruses,67 and have reduced levels of stress indicators (including systolic blood pressure and noradrenaline and cortisol levels).68 Across multiple studies, negative feelings decrease and positive emotions increase.69 Forest walking within urban parks was found to ease acute emotions (such as boredom and depression), and the higher the self-reported stress level, the greater the positive effect.19

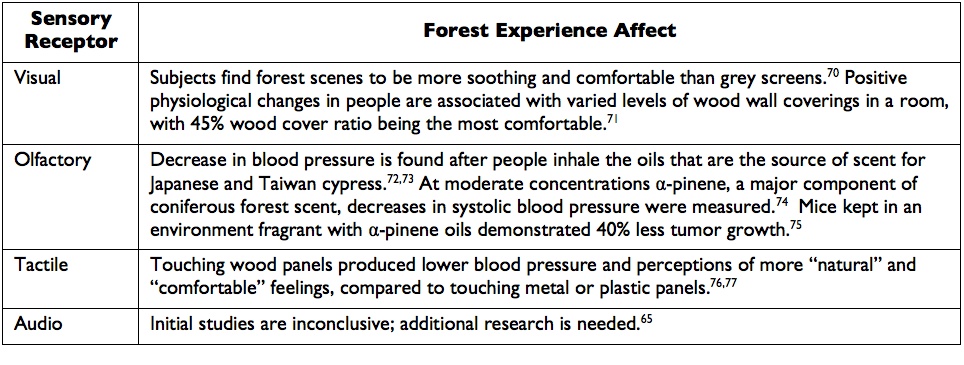

Effects of shinrin-yoku have also been examined in laboratory experiments. Tests have isolated the visual, olfactory, and tactile reactions of people to forest components. Table 3 summarizes findings:

Table 3: Benefits results from multiple studies about forest bathing in Japan.

Theories about Restorative Nature Effects

We reviewed more than 200 empirical publications to prepare this report. Across nations, decades, and people of all ages, socioeconomic conditions, and residence types, the studies show correlation of nearby nature experiences with reduced stress and improved wellness. Why do these effects occur? How do we explain such responses? Many articles invoked two established theories, both supporting the premise that green spaces are especially conducive to recovery from life’s pressures.78

Rachel and Stephen Kaplan propose the attention restoration theory (ART) to explain responses to the effects of natural settings.79 This theory focuses on cognitive processes and proposes that our capacity for mental attention can be depleted by activities demanding prolonged, effortful focus — leading to fatigue, frustration, and inability to concentrate. Restorative environments have four components: being away, extent, compatibility, and fascination. The last of these is essential for cognitive recovery; a setting having fascinating qualities attracts involuntary attention, which demands less mental effort. Nature attracts one’s attention because of its “soft fascination,” providing the opportunity for recovery from mental fatigue.80

Roger Ulrich suggests the stress reduction theory (SRT) to explain emotional and physiological reactions to natural spaces.4 Being in an unthreatening natural environment or viewing natural elements (such as vegetation or water) activates a positive affective response, an inclination to approach such natural elements, and sustained, wakefully relaxed attention. Individuals then can experience a decrease in stress, which involves reduced levels of negatively toned feelings and reductions in elevated physiological conditions (such as heart rate and blood pressure).

The two theories have common features, but they differ in claims of the innate sources of nature response, and emphasize different restorative outcomes.81,20 Each theory is conceptually distinct and yet describes conditions related to the other. Both theories offer thoughtful and plausible explanations about why so many studies detect positive human response to the presence of nature.

References

1. Ulrich, R.S., and R. Parsons. 1992. Influences of Passive Experiences with Plants on Individual Well-being and Health. In: D. Relf (Ed.) The Role of Horticulture in Human Well-being and Social Development: A National Symposium. Arlington, VA, Timber Press, pp. 93-103.

2. Glacken, C.J. 1967. Traces on the Rhodian Shore: Nature and Culture in Western Thought From Ancient Times to the End of the Eighteenth Century. University of California Press.

3. Hickman, C. 2013. To Brighten the Aspect of Our Streets and Increase the Health and Enjoyment of Our City: The National Health Society and Urban Green Space in Late-nineteenth Century London. Landscape and Urban Planning 118:112-19.

4. Ulrich, R.S., R.F. Simons, B.D. Losito, E. Fiorito, M.A. Miles, and M. Zelson. 1991. Stress Recovery During Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology 11, 3:201-230.

5. Baum, A., R. Fleming, and J.E. Singer. 1985. Understanding Environmental Stress: Strategies for Conceptual and Methodological Integration. In: A. Baum and J.E. Singer (Eds.) Advances in Environmental Psychology Vol. 5: Methods and Environmental Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 185-205.

6. Grahn, P., and U.A. Stigsdotter. 2003. Landscape Planning and Stress. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2, 1:1-18.

7. McEwen, B.S. 2004. Protection and Damage From Acute and Chronic Stress: Allostasis and Allostatic Overload and Relevance to the Pathophysiology of Psychiatric Disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1032:1-7.

8. Steptoe, A., and P.J. Feldman. 2001. Neighborhood Problems as Sources of Chronic Stress: Development of a Measure of Neighborhood Problems, and Associations with Socioeconomic Status and Health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 23, 3:177-185.

9. Cohen, S. 1978. Environmental Load and the Allocation of Attention. In A. Baum, J.E. Singer, and S. Valins (Eds.) Advances in Environmental Psychology. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, New Jersey, Lawrence Erlbaum.

10. Lederbogen, F., P. Kirsch, L. Haddad, et al. 2011. City Living and Urban Upbringing Affect Neural Social Stress Processing in Humans. Nature 474, 7352:498-501.

11. Sauter, S.L., L. Murphy, et al. 1999. Stress... at Work. DHHS Publication No. 99-101. Cincinnati, OH, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 26 pp.

12. Kweon, B.S., R S. Ulrich, V.D. Walker, and L.G. Tassinary. 2008. Anger and Stress: The Role of Landscape Posters in An Office Setting. Environment and Behavior 40, 3:355-381.

13. McGonagle, K.A., and R.C. Kessler. 1990. Chronic Stress, Acute Stress, and Depressive Symptoms. American Journal of Community Psychology 18, 5:681-706.

14. Steptoe, A, and P.J. Feldman. 2001. Neighborhood Problems as Sources of Chronic Stress: Development of a Measure of Neighborhood Problems, and Associations with Socioeconomic Status and Health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 23, 3:177-185.

15. Aldwin, C.M. 2009. Stress, Coping, and Development: An Integrative Approach. New York, Guilford, 432 pp.

16. Collingwood, J. 2007. The Physical Effects of Long-Term Stress. Psych Central. Retrieved on December 5, 2013, from http://psychcentral.com/lib/the-physical-effects-of-long-term-stress/000935.

17. Aldwin, C.M. 2009. Stress, Coping, and Development: An Integrative Approach. New York, Guilford, 432 pp.

18. Tsigos, C., and G.P. Chrouso. 2002. Stress, the Endoplasmic Reticulum, and Insulin Resistance. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 53:865–871.

19. Morita, E., S. Fukuda, J. Nagano, et al. 2007. Psychological Effects of Forest Environments on Healthy Adults: Shinrin-Yoku (Forest-Air Bathing, Walking) As a Possible Method of Stress Reduction. Public Health 121, 1:54-63.

20. Hartig, T., G.W. Evans, L.D. Jamner, D.S. Davis, and T. Gärling. 2003. Tracking Restoration in Natural and Urban Field Settings. Journal of Environmental Psychology 23, 2:109-123.

21. Kahn, Jr., P.H., B. Friedman, B. Gill, et al. 2008. A Plasma Display Window? The Shifting Baseline Problem in a Technologically Mediated Natural World. Journal of Environmental Psychology 28, 2:192-199.

22. Alvarsson, J.J., S. Wiens, and M.E. Nilsson. 2010. Stress Recovery During Exposure to Nature Sound and Environmental Noise. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 7, 3:1036-046.

23. Ulrich, R.S., R.F. Simons, and M. Miles. 2003. Effects of Environmental Simulations and Television on Blood Donor Stress. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 20, 1:38-47.

24. Parsons, R., L.G. Tassinary, R.S. Ulrich, M.R. Hebl, and M. Grossman-Alexander. 1998. The View From the Road: Implication for Stress Recovery and Immunization. Journal of Environmental Psychology 18, 2:113-140.

25. Kjellgren, A., and H. Buhrkall. 2010. A Comparison of the Restorative Effect of a Natural Environment with a Simulated Natural Environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology 30, 4:464-472.

26. World Health Organization. 2006. Obesity and Overweight. Fact Sheet 311. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en.

27. World Health Organization. 2008. Depression: Programmes and Projects. Mental Health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental health/management/depression/definition/en/.

28. Sahlin M. 2001. Plan mot den ökade stressen i arbetslivet (Plan to Fight Increasing Stress in Working Life) [In Swedish]. DN debatt, Dagens Nyheter 31:5.

29. Wu S.Y., and A. Green. 2000. Projection of Chronic Illness Prevalence and Cost Inflation. Santa Monica, CA, RAND Health.

30. Centers for Disease Control. Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm.

31. Ulrich, R.S., and D.L. Addoms. 1981. Psychological and Recreational Benefits of a Residential Park. Journal of Leisure Research 13, 1:43-65.

32. Ulrich, R.S. 1979. Visual Landscapes and Psychological Well-Being. Landscape Research 4, 1:17-23.

33. Ulrich, R.S. 1986. Human Responses to Vegetation and Landscapes. Landscape and Urban Planning 13:29-44.

34. Roe, J.J., C.W. Thompson, P.A. Aspinall, M.J. Brewer, E.I. Duff, D. Miller, R. Mitchell, and A. Clow. 2013. Green Space and Stress: Evidence From Cortisol Measures in Deprived Urban Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10, 9:4086-4103.

35. Kuo, F.E. 2001. Coping with Poverty: Impacts of Environment and Attention in the Inner City. Environment and Behavior 33, 1:5-34.

36. Aspinall, P., P. Mavros, R. Coyne, and J. Roe. 2013. The Urban Brain: Analysing Outdoor Physical Activity with Mobile EEG. British Journal of Sports Medicine. DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091877.

37. Hansmann, R., S.M. Hug, and K. Seeland. 2007. Restoration and Stress Relief Through Physical Activities in Forests and Parks. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 6, 4:213-225.

38. de Vries, S., R.A. Verheij, P.P. Groenewegen, and P. Spreeuwenberg. 2003. Natural Environments-Healthy Environments? An Exploratory Analysis of the Relationship Between Greenspace and Health. Environment and Planning A 35, 10:1717-1732.

39. Korpela, K.M., M. Ylén, L. Tyrväinen, and H. Silvennoinen. 2008. Determinants of Restorative Experiences in Everyday Favorite Places. Health & Place 14, 4:636-652.

40. Hauru, K., S. Lehvävirta, K. Korpela, and D.J. Kotze. 2012. Closure of View to the Urban Matrix Has Positive Effects on Perceived Restorativeness in Urban Forests in Helsinki, Finland. Landscape and Urban Planning 107:361-69.

41. Fan, Y., K.V. Das, and Q. Chen. 2011. Neighborhood Green, Social Support, Physical Activity, and Stress: Assessing the Cumulative Impact. Health & Place 17, 6:1202-211.

42. Mitchell, R., T. Astell-Burt, and E.A. Richardson. 2011. A Comparison of Green Space Indicators for Epidemiological Research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 65, 10:853-58.

43. Paquet, C., T.P. Orschulok, N.T. Coffee, N.J. Howard, G. Hugo, A.W. Taylor, R.J. Adams, and M. Daniel. 2013. Are Accessibility and Characteristics of Public Open Spaces Associated with a Better Cardiometabolic Health? Landscape and Urban Planning 118:70-78.

44. Talbot, J.F., and R. Kaplan. 1986. Judging the Sizes of Urban Open Areas: Is Bigger Always Better? Landscape Journal 5, 2:83-92.

45. Maas, J., R.A. Verheji, S. de Vries, P. Spreeuwenberg, F.G. Schellevis, and P.P. Groenewegen. 2009. Morbidity Is Related to a Green Living Environment. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 63:967-973.

46. Astell-Burt, T., X. Feng, and G.S. Kolt. 2013. Is Neighbourhood Green Space Associated with a Lower Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus? Evidence from 267,072 Australians. Diabetes Care 37, 1:197-201.

47. Donovan, G.H., Y.L. Michael, D.T. Butry, A.D. Sullivan, and J.M. Chase. 2011. Urban Trees and the Risk of Poor Birth Outcomes. Health & Place 17, 1:390-93.

48. Dadvand, P., A. de Nazelle, F. Figueras, X. Basagaña, J. Su, E. Amoly, M. Jerrett, M. Vrijheid, J. Sunyer, and M.J. Nieuwenhuijsen. 2012. Green Space, Health Inequality and Pregnancy. Environment International 40:110-15.

49. Stasionyte, J., J. Vencloviene, A. Dedele, and R. Kubilius. 2013. The Effect of Urban Green Space and the Risk for Cardiovascular Death in One Year Period. Global Journal on Advances in Pure and Applied Sciences 13, 1:20.

50. Nielsen, T.S., and K.B. Hansen. 2007. Do Green Areas Affect Health? Results From a Danish Survey on the Use of Green Areas and Health Indicators. Health & Place13, 4:839-50.

51. Wells, N.M., and G W. Evans. 2003. Nearby Nature: A Buffer of Life Stress Among Rural Children. Environment and Behavior 35, 3:311-330.

52. Agyemang, C., C. Van Hooijdonk, W. Wendel-Vos, J.K. Ujcic-Voortman, E. Lindeman, K. Stronks, and M. Droomers. 2007. Ethnic Differences in the Effect of Environmental Stressors on Blood Pressure and Hypertension in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 7, 1:118-128.

53. Donovan, G.H., D.T. Butry, Y.L. Michael, J.P. Prestemon, A.M. Liebhold, D. Gatziolis, and M.Y. Mao. 2013. The Relationship Between Trees and Human Health: Evidence From the Spread of the Emerald Ash Borer. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 44, 2:139-145.

54. Gidlöf-Gunnarsson, A., and E. Öhrström. 2007. Noise and Well-Being in Urban Residential Environments: The Potential Role of Perceived Availability to Nearby Green Areas. Landscape and Urban Planning 83, 2-3:115-126.

55. Wheeler, B.W., M. White, W. Stahl-Timmins, and M.H. Depledge. 2012. Does Living by the Coast Improve Health and Wellbeing? Health & Place 18, 5:1198-1201.

56. Hipp, J.A., and O.A. Ogunseitan. 2011. Effect of Environmental Conditions on Perceived Psychological Restorativeness of Coastal Parks. Journal of Environmental Psychology 31, 4:421-29.

57. Van den Berg, A.E., T. Hartig, and H. Staats. 2007. Preference for Nature in Urbanized Societies: Stress, Restoration, and the Pursuit of Sustainability. Journal of Social Issues 63, 1:79-96.

58. Hernández, B., and M.C. Hidalgo. 2005. Effect of Urban Vegetation on Psychological Restorativeness. Psychological Reports 96, 3 Pt 2:1025-28.

59. Hug, S.M., T. Hartig, R. Hansmann, K. Seeland, and R. Hornung. 2009. Restorative Qualities of Indoor and Outdoor Exercise Settings As Predictors of Exercise Frequency. Health & Place 15, 4:971-980.

60. Adevi, A.A., and P. Grahn. 2011. Attachment to Certain Natural Environments: A Basis for Choice of Recreational Settings, Activities and Restoration From Stress? Environment and Natural Resources Research 1, 1:36-52.

61. Gathright, J., Y. Yamada, and M. Morita. 2006. Comparison of the Physiological and Psychological Benefits of Tree and Tower Climbing. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 5, 3:141-149.

62. Pillemer, K., T.E. Fuller-Rowell, M.C. Reid, and N.M. Wells. 2010. Environmental Volunteering and Health Outcomes Over a 20-Year Period. The Gerontologist 50, 5:594-602.

63. Wakefield, S., F. Yeudall, C. Taron, J. Reynolds, and A. Skinner. 2007. Growing Urban Health: Community Gardening in South-East Toronto. Health Promotion International 22, 2:92-101.

64. Hawkins, J.L., K.J. Thirlaway, K. Backx, and D.A. Clayton. 2011. Allotment Gardening and Other Leisure Activities for Stress Reduction and Healthy Aging. HortTechnology 21, 5:577-585.

65. Tsunetsugu, Y., B.J. Park, and Y. Miyazaki. 2010. Trends in Research Related to “Shinrin-Yoku” (Taking in the Forest Atmosphere or Forest Bathing) in Japan. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine 15, 1:27-37.

66. Ohtsuka, Y., N. Yabunaka, and S. Takayama. 1998. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest-Air Bathing and Walking) Effectively Decreases Blood Glucose Levels in Diabetic Patients. International Journal of Biometeorology 41, 3:125-7.

67. Li, Q., M. Kobayashi, H. Inagaki, Y. Hirata, Y.J. Li, K. Hirata, T. Shimizu, H. Suzuki, M. Katsumata, Y. Wakayama, T. Kawada, T. Ohira, N. Matsui, and T. Kagawa. 2010. A Day Trip to a Forest Park Increases Human Natural Killer Activity and the Expression of Anti-cancer Proteins in Male Subjects. Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents 24, 2:157-166.

68. Park, B.J., Y. Tsunetsugu, T. Kasetani, T. Kagawa, and Y. Miyazaki. 2010. The Physiological Effects of Shinrin-yoku (Taking in the Forest Atmosphere or Forest Bathing): Evidence From Field Experiments in 24 Forests Across Japan. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine 15, 1:18-26.

69. Tsunetsugu, Y., J. Lee, B.-J. Park, L. Tyrväinen, T. Kagawa, and Y. Miyazaki. 2013. Physiological and Psychological Effects of Viewing Urban Forest Landscapes Assessed by Multiple Measurements. Landscape and Urban Planning 113:90-93.

70. Suda, R., M. Yamaguchi, E. Hatakeyama, T. Kikuchi, Y. Miyazaki, and M. Sato. 2001. Effect of Visual Stimulation (I)-In the Case of Good Correlation Between Sensory Evaluation and Physiological Response. Journal of Physiological Anthropology 20, 5:303.

71. Tsunetsugu, Y., Y. Miyazaki, and H. Sato. 2005. Visual Effects of Interior Design in Actual-Size Living Rooms on Physiological Responses. Building and Environment 40:1341-46.

72. Miyazaki, Y., Y. Motohashi, and S. Kobayashi. 1992. Changes in Mood by Inhalation of Essential Oils in Humans II. Effect of Essential Oils on Blood Pressure, Heart Rate, RR Intervals, Performance, Sensory Evaluation and POMS. Journal Japan Wood Research Society 38: 909-13.

73. Miyazaki, Y., T. Morikawa, and N. Yamamoto. 1999. Effect of Wooden Odoriferous Substances on Humans. Japanese Journal of Physiological Anthropology 4:49-50.

74. Tsunetsugu Y., T. Morikawa, and Y. Miyazaki. 2005. The Relaxing Effect of the Smell of Wood. Wood Industry 60, 11:598–602.

75. Kusuhara, M., K. Urakami, Y. Masuda, V. Zangiacomi, H. Ishii, S. Tai, K. Maruyama, and K. Yamaguchi. 2012. Fragrant Environment with Α-pinene Decreases Tumor Growth in Mice. Biomedical Research 33, 1:57-61.

76. Sakuragawa, S., T. Kaneko, and Y. Miyazaki. 2008. Effects of Contact with Wood on Blood Pressure and Subjective Evaluation. Journal of Wood Science 54, 2:107-113.

77. Miyazaki, M.T., T. Morikawa, and S. Sueyoshi. 1999. Effect of Touching to Wood on Humans. Japan Society of Physiological Anthropology 1, 4:51-52.

78. Bratman, G.N., J.P. Hamilton, and G.C. Daily. 2012. The Impacts of Nature Experience on Human Cognitive Function and Mental Health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1249:118-136.

79. Kaplan, R., and S. Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. New York, Cambridge University Press.

80. Kaplan, S. 1995. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward An Integrative Framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 15, 3:169-182.

81. Hartig, T., and G.W. Evans. 1993. Psychological Foundations of Nature Experience. In T. Garling, and R.G. Golledge (Eds.) Behavior and Environment: Psychological and Geographical Approaches. Amsterdam, Elsevier, pp 427–457.

82. Lepore, S.J., H.J. Miles, and J.S. Levy. 1997. Relation of Chronic and Episodic Stressors to Psychological Distress, Reactivity, and Health Problems. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 4, 1:39-59.

83. Ohira, H., S. Takagi, K. Masui, M. Oishi, and A. Obata. 1999. Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Forest-Air Bathing and Walking) on Mental and Physical Health. Bulletin of Tokai Women's University 19:217-232.

84. Richardson, E.A., and R. Mitchell. 2010. Gender Differences in Relationships Between Urban Green Space and Health in the United Kingdom. Social Science & Medicine 71, 3:568-575.

85. Tamosiunas, A., R. Grazuleviciene, D. Luksiene, et al. 2014. Accessibility and Use of Urban Green Spaces, and Cardiovascular Health: Findings From a Kaunas Cohort Study. Environmental Health 13, 1: 20.

86. Donovan, G.H., D.T. Butry, Y.L. Michael, J.P. Prestemon, A.M. Liebhold, D. Gatziolis, and M.Y. Mao. 2013. The Relationship Between Trees and Human Health: Evidence From the Spread of the Emerald Ash Borer. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 44, 2:139-145.

The World Health Organization identifies stress and low physical activity as two of the leading contributors to premature death in developed nations

The cumulative effect of chronic, low-grade stresses, with little opportunity for recovery, can lead to unhealthy psychological and physiological reactions

Exposure to nearby nature can effectively reduce stress particularly if initial stress levels are high - simply having a view of nature produces recovery benefits

People experiencing high stress can also benefit from being physically active in a nature setting

Individuals experience a greater degree of restorative experience and lower stress levels after longer and more frequent visits to green spaces

Exercising in a green environment appears to enhance the restorative effects of urban greenery, and more restorative outdoor settings may boost exercise frequency

|

|

Public housing residents with nearby trees and grass were more effective in coping with major life issues compared to those with homes surrounded by concrete

Moms having nearby green space and trees may have a positive effect on infant birth weight

Studies in Japan of 'shinrin-yoku" or "forest bathing" have found effects of improved immune system response, lowered stress indicators, reduced depression, and lower glucose levels in diabetics

nearby nature experiences can improve stress response for people at all stages in the human life cycle

Stewardship volunteering is positively related to physical activity and better health and depression symptoms, especially among mid-life volunteers

Gardening can be a part of healthy aging - stress levels decreased significantly for people between 50 and 88 years old who maintained a community garden plot compared with those who exercised indoors